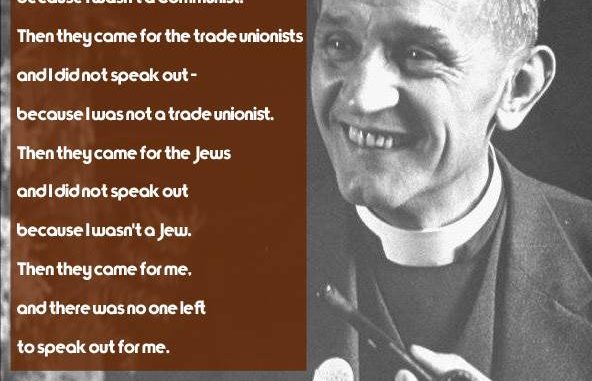

The man behind that anti-Nazi poem. Martin Niemöller.

Niemoller is the author of one of the most famous poems of the twentieth century (full text below) but it occurred to me that for most of us that is the limit of our knowledge about the man – so let’s take a quick look at his surprising life.

…

Niemoller was not always a Lutherian pastor, during WWI he was a submarine commander and was awarded the highest military honour, the Iron Cross, first class. In fact, he wrote a book about the transition called “From U-boat to Pulpit” published in 1933.

In the final chapter of this book he praised the Nazis and welcomed their victory as a “national revival”. This was not a passing fancy as he was swept along with the tide either. In 1920, four years before being ordained, he was a volunteer for the Freikorps, right-wing paramilitaries who violently suppressed the communist uprisings. His politics were solidly anti-communist and conservative.

In the 1932, before the Nazi’s seizure of power, Niemoller personally met with Hitler where he was promised that the Nazis would not interfere with the church. Niemoller also claimed that Hitler had promised him that there would not be pogroms against the Jews saying “There will be restrictions against the Jews, but there will be no ghettos, no pogroms, in Germany.”

His enthusiasm quickly waned when the Nazis took power as they arrested 800 pastors of Niemoller’s church and he founded the defence organisation The Pastor’s Emergency League. By the end of 1934, horrified by the new regime, he formed an organisation to defend Christians of a Jewish background and was a leading part of founding the Confessional Church – an explicitly Christian anti-Nazi organisation which described the worship of the Fuhrer and the cult of the Aryan “superman” as “an insane belief [that] creates a god from man’s being” and most dangerously denounced Nazism itself as “anti-Christian”.

Don’t think that this meant he had become a saint though, it took him some time to re-examine his anti-Communist and anti-Semitic politics and even in 1935 he used a sermon to denounce Jews as the killers of Christ.

…

He was finally arrested on the personal orders of Hitler himself after an “inflammatory” sermon and wire tapping revealed he was involved in organised resistance. 500 pastors read out his sermon from their own pulpits in the weeks following his arrest.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who Niemoller had set up the new church with, went underground and set up anti-Nazi resistance cells. He was eventually arrested and executed for plotting to assassinate Hitler.

Niemoller on the other hand was first sent to a torture prison in Berlin, then released and immediately rearrested by the gestapo on the court house steps to be sent for “re-education” but when he was found to be “unreformable” he was finally sent to the Dachau death camp.

In the last days of the war the SS rounded up over a hundred prisoners, Niemoller among them, and took them with them as they fled, probably to use as hostages with orders to kill them all if it looked like they were to be liberated. Ordinary German soldiers, regulars, stepped in and took the prisoners away from the SS and into protective custody saving Niemoller’s, and everyone else’s, lives.

After the war Niemoller began a process of atonement and was the prime mover behind the Stuttgart Declaration of Guilt, declaring that Germans had to face up to their complicity before they could truly ask for God’s forgiveness. He toured the country and was regularly heckled as he gave sermons on the theme.

For instance, he declared “We must openly declare that we are not innocent of the Nazi murders, of the murder of German communists, Poles, Jews, and the people in German-occupied countries. No doubt others made mistakes too, but the wave of crime started here and here it reached its highest peak. The guilt exists, there is no doubt about that — even if there were no other guilt than that of the six million clay urns containing the ashes of incinerated Jews from all over Europe. And this guilt lies heavily upon the German people and the German name, even upon Christendom. For in our world and in our name have these things been done.”

He meant that poem – he really felt that he was complicit, despite his later resistance. Of his own political transformation he said;

“I have never concealed the fact and said it before the court in 1938 that I came from an anti-Semitic past and tradition… I ask only that you look at my life historically and take it as history. I believe that from 1933 I truly represented the Lutheran-Christian outlook on the Jewish question… but that I returned home after eight years’ imprisonment as a completely different person.”

He also said; “I began my political responsibility as an ultra-conservative. I wanted the Kaiser to come back; and now I am a revolutionary. I really mean that. If I live to be a hundred I shall maybe be an anarchist, for an anarchist wants to do without all government.”

During the Vietnam War (or The American War if you’re Vietnamese) he drove the US authorities wild when he made a personal visit to Ho Chi Minh and called for peace.

He spent many years campaigning for nuclear disarmament. Saying “We had been frightened of atomic weapons since 1945. In those days I became convinced — and remain convinced now — that, after Hitler, Truman was the greatest murderer in the world.”

…

One final note, on the poem itself. You will be aware that it appears in many different forms, often with a different first line or mentioning different groups (Catholics, gay people, etc.) and often in a different order. Partly this is down to political taste, many didn’t want to mention the Communists and some found it weird that the Jews were so far down the list… but the core reason why this is possible was that it was never a poem at all.

It is in fact based on an interview Niemoller gave not long after the war had ended and was never transcribed only recalled by the journalist. Even Niemoller himself did not know which was the “real” version, although the one I’ve printed here was apparently his preferred text.

Whatever the truth of this extraordinary poem it still stands as both an injunction against inaction and a testament that even the most reactionary person, a nationalist war hero and right-wing paramilitary can end up one of the most high profile anti-Nazis at a time when to speak out meant to give everything to resistance.